Press

Following the Brush | One-Person Show

RAWLS MUSEUM ARTS, COURTLAND, VA

In his one-man show, John Adams Visits Richmond, at the Martha Mabey Gallery in 1994, there were fifteen John Adams paintings, seven of which have been borrowed for this show. “The John Adams that got loose in my studio in 1977 has been one vehicle I have used to express feelings, ranging from those that express the felicity of life to those that express the finality of death.” Five paintings are from his 1995 one-man show, Flesh and Vegetation, at the Fulcrum Gallery. There are also paintings in this show from his 1998 show, Figures and Earthen Elements, at the Main Art Gallery. These paintings were inspired by the rejuvenation of springtime, that season of annual exuberance when we feel our life has another chance to be fulfilled. This series starts with “Easter Lily” and continues with paintings relating to feelings that were generated by springtime.

His most recent show at Cudahy’s Gallery in Richmond featured the Oaxaca series, a group of paintings that were inspired by small clay heads created by the indigenous people of Oaxaca, Mexico, and that date from 1000 BC to 100 AD. “I used these Oaxacan heads in my studio as an inspirational source for the figures in this series of paintings, and found new vehicles to express those inner feelings that are always searching for ways to spontaneously break out.” There are two new paintings from the Oaxaca series in this show, Following the Brush.

“My painting goal is to express feelings and emotions and to do so through a painting process of changing and distorting images of the visual world, using color for emphasis and enhancement in order to bring form and structure to those images that come from within. I seek to bring visual form to that which is not visual and to bring to the painting that quality of fluidity captured, creating a surface vitality, a living skin that I think can be so wonderfully unique to oil painting."

Portrait of the Artist as a Changing Man

BY SHARON BRICKER

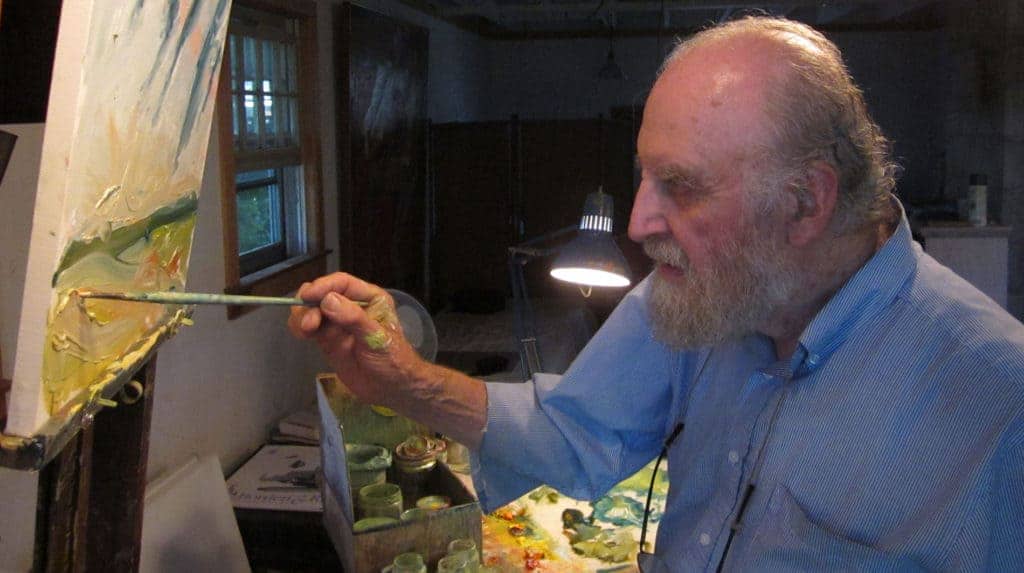

At the Nov.6 opening of his show at Richmond’s Main Art Gallery, titled “Paintings of Figures and Earthen Elements,” I took turns studying Christus Murphy and his artwork.

As he circulated among the people looking at the images of women and landscapes, his long, white beard seemed at odds with his trim shape and lithe movements. I found myself explaining Murphy’s imagery to a friend; I couldn’t help talking about everything I had learned in the past two days, picking the artist’s brain in his Main Street studio.

The studio barely has space for its giant easel and the large works that are created on it. “I’m basically a symbolist,” he said. “I try to express feelings from within. An image may be carried in my mind years before I paint it.”

For instance, in the painting “The Cut Tree and Chain Link Fence,” a tree that had grown through a fence had been gnarled and misshapen by cutting it back. Murphy discovered the scene and was touched.

“What remained was like a torso. What I felt was a crucifixion.” He knew he would use it as a symbol someday, and it was brought to this canvas to convey a crucifixion and the Holocaust -- man’s inhumanity to man, he said. Brushstrokes of red shine on the ends of the tree branches.

“It’s difficult for me to paint a negative painting,” he said. “I always feel some hope that as bad as people are sometimes, the species can be saved.”

Murphy’s work is filled with symbolism, and he explained the origin of his symbols carefully. While working on one of his crucifixion trees, he included a floating blue square in the composition.

“I don’t know what inspired me to create those shapes,” he said. “But later on, I got a book of [Carl] Jung’s symbols, and he brought up a blue cube--a symbol of God.” Murphy quoted Joseph Campbell, an American mythologist, who said that symbols are the spontaneous product of the human psyche. It’s apparent in the artist’s excitement that the revelation impacted his work.

>“I think you would call many of my paintings expressionistic surrealism,” Murphy said. As a student at the Massachusetts College of Art in the early 1950s, he was influenced by the growth of the Abstract Expressionist movement, which embraced the individual’s expression through the act of painting.

When asked about how he felt about having a traditional art education, with the usual realist training, he found it valuable in developing his skills, but “Most students are rebels, and I think it’s healthy,” he said.

After graduating in 1953, he painted as much as he could and exhibited a number of times in his native Massachusetts for the rest of the decade. He spent a year and a half after that traveling in Italy and Spain, pursuing an interest in Italio Byzantine art with his first wife.

“My first reaction was that I didn’t really understand [the Italians’] social values,” he said. “They have a certain kind of trickery that’s wonderful, but it throws you off. The Italians have the ability to enjoy life; work is a pleasure. They’re beautiful people.”

Despite his surroundings, Murphy began to feel dissatisfied with his artwork. The line between what makes a painting professional and what makes it a masterpiece is so vague, he said, that as a young painter, he often felt bombarded by doubts about his abilities.

He went to the Sistine Chapel to see Michelangelo’s “Last Judgment,” and found it overwhelming. “It’s huge, and every inch is a masterpiece,” he said. “I thought, ‘Why am I trying to do what I’m doing, when I’m competing with that? Why bother?”

A friend from Italy invited him to visit in the Canary Islands for five months, where he was interviewed four times and given studio space to work in at a school. The students even framed all of his pieces for a sold-out show, he said gratefully.

Still, he was becoming increasingly frustrated with his work. “The image in my mind and what I could put on the canvas were too different,” he said. “I could have sold 10 times the number of paintings I sold, and still have been confronted with the same doubts.

“There was no justification for me to go on doing what I was doing,” he said. Knowing what Michelangelo had done only made it easier for him to make a decision: at the age of 27, he gave up painting for the next 17 years.

Murphy worked as an illustrator and account executive at an advertising agency in Boston, which gave him financial security, but not fulfillment. He recalls taking a break from work outside one day and having a rare moment to reflect, while watching sticks in the gutter.

“It reminded me of when I was a child, and I used to race sticks down the gutter... It made me question what I had done from when I was a child up until that point. Why did everything I had done in my life lead me to where I was at that moment?

“If there is any justification for my existence in this world, [painting] is the best one. I was not doing what I should have been doing with my life,” he said. “I felt quite strongly that I had to change it.”

After some deliberation, in 1977, he set up a studio and began to paint again. He started over, this time with skills that were improved by the illustration business.

“I’ve sort of gone through a cycle,” he said. “Now I have the same desires [in painting] I had as a young man, but I have skills and knowledge as a painter that I didn’t have then.

“All I’m trying to do is paint what’s within me -- and whether I compare with Michelangelo or not is irrelevant,” he said.

One of his first efforts, “Lone Figure on Stage,” shows a figure collapsed on a stage, a thin arch surrounding him, and a bag next to him that he seems to be leaking into. Murphy said the figure is a symbol of himself on the stage of life, separated from the powers he should be sensitive to.

“We shield ourselves from the beautiful and magical aspects of life by what we’re doing,” he said, motioning at the large canvas. “I was emotionally whipped after I finished it.” He wanted his next project to be an abstraction, just to enjoy putting paint on the canvas again.

When he saw the newspaper picture of composer and conductor John Adams in a package he received, he was excited by elements of the photograph and decided to use it as an idea for this abstraction. But the piece evolved into “John Adams Gets Loose In My Studio,” the strong start of a series of about 15 John Adams paintings.

“I discovered that I could use the John Adams figure as a vehicle to express whatever I wanted to,” he said. Adams’ dynamic gestures, expressive mouth and total absorption in his task provided a vehicle to carry Murphy’s emotions into his compositions.

Between 1976 and 1986, Murphy lived a life he described as divided into the two halves of his studio: the painting side and the illustration-and-moneymaking side. Murphy laughed about the cycle he worked in.

“If I really needed money, I’d get on the phone and hustle [to sell freelance illustrations]. Once I got my billing up, I’d go back to the easel and paint. Some time later, I’d wake up in a cold sweat and realize I had to get my billing up again.”

Then, one day, while he was walking to get some coffee as a break from painting, he was hit by a bicycle and knocked out cold. He woke up in a hospital bed, with a collarbone loosened by the severing of three ligaments in his right shoulder. He paints and illustrates with his right arm.

“There’s a certain kind of facility you need to illustrate that was severely bothered by the accident,” he said. Janet, his wife, decided she needed a steadier job than the acting and teaching she did in Boston, in case she had to support her husband and son Jonathan (now 15 years old). Her job hunt led the family to Richmond, where Janet now teaches voice and speech at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Despite having the end of his collarbone removed to allow his arm to function, he said it works beautifully now. However, he was on disability for a year and a half before he could work again.

Martha Mabey, former Richmond gallery owner, discovered Murphy’s work after meeting his wife at her Carytown gallery. She fell in love with his paintings and exhibited Murphy’s work a number of times, including a one-man show focused on his John Adams pieces in Jan. 1995. The shows sold so well that Murphy was able to put aside the freelance illustration and paint full-time, although he has done several jobs since then.

His paintings have been used for several theater productions’ posters, such as “Molly Sweeny,” a play by Brian Friel at the Barksdale Theatre.

Murphy still has a strong vision for where he wants his artwork to go. Without so much as a moment’s hesitation to collect his thoughts, he described three elements of the perfect painting he aspires to create: Paul Cezanne’s plasticity, John Singer Sargent’s fluidity, and a touch of eternal truth, which he believes all great paintings have -- “something that reaches us and we understand.”

When asked what he does to escape painting, he furrowed his brow and tried to explain what most of us will never experience. “Some people work to live, and some live to work. I fall in that category; painting is what I find fulfilling... it would be easy for me to do nothing but paint.”

Christus Murphy at the Fulcrum Gallery

BY MARTHA MABEY

Boston ex-patriot, Christus Murphy, is an artist in a hurry. “Flesh & Vegetation,” his current exhibition of oil paintings at Fulcrum Gallery covers such a range of new work that it could be four distinct shows. First of all, there are his nudes. Like Renoir’s luscious exaltation of the female form, Murphy’s sensuous renderings are enhanced by a palette of spring-like colors that makes the warm, fleshy curves of his figures almost pure in their clarity and physicality. Color and form seem to melt in a liquid distortion of the female shape that is as pleasing as it is unsettling and is in direct contrast with the current American media image of woman as hard, emaciated and flat-chested. Murphy is a man who loves women.

His celebration of the vitality of life so evident in his nudes extends to the exhibit’s three small landscapes. Painted with simple energetic strokes in breathtakingly vibrant pinks and greens, they glow with the brightness and freshness of spring. This is particularly true of “Sunset on the Marsh” which features a satisfying, but odd image visible in Murphy’s paintings for years--a small blue cube—his representation of the spirit or life force coming into existence.

Then there are his portraits: a suggestion of Modigliani greets the viewer in the coy pair, “Boston Woman in Green Chair” and “Woman in Green Chair”. There is also a surprising nod to the Dutch Masters in the exquisite oil and conte crayon “Head Study for April’s Child.” Five “Chemise” paintings displayed together in Andy Warhol fashion also delight the eye without challenging the viewer. And while the mysteriously beautiful “Gypsy Room” is the most sensuous in the show, it, too, is pleasing without being confrontive.

On the other hand, the viewer is definitely challenged, confronted, and charged emotionally by the exhibition’s most powerful paintings: “The Path,” “The Passing,” and “The Cut Tree and Chain Link Fence.” Each of these paintings warrants comment. “The Path” features a female figure leaning against—or entwined with—a tree which is separated from a cypress-framed sunset by a wall or window. Beautifully painted and highly symbolic, “The Path” hints at the union between the physical and the spiritual. The same elements—wall, window, tree, entwined figure—reappear in the most emotionally poignant work in the show, “The Cut Tree and Chain Link Fence”. Whether viewed as a statement about the crucifixion or the holocaust, it suggests suffering humanity and deserves close study by the viewer. “The Passing,” which features a formal Renaissance angelic figure above a neatly made-up hospital bed, is painted in the lively pinks and greens which permeate the entire exhibit, and like the other paintings, seems to celebrate new life. It is this celebration of the vitality of life that ultimately ties all of Murphy’s work together and leaves the viewer with a sense of joy and wonder.

Newspaper Articles

Loading Dock Celebrates Second Year

BOSTON GLOBE, MAY 1982